Change, making progress, moving forward. Good, desirable things. You’d be hard pressed to find anybody who would voice opposition to them. Yet, change is seldom easy and rarely straightforward. Why?

“I am not sure about X”, “I need to understand more about Y”, “I have questions about Z”. Those lines, and many others like them, are staples from the tribe of the progress prevention officers, the unable to decide and the scared to decide crowd. Many times, those with a bias for more analysis have inflicted degrees of paralysis on proceedings and made themselves the scourge of my professional life.

Some folks though seem to have only one level of detail; complete, thorough, all questions answered. Too much detail though is a dangerous thing because we know that plan A almost never survives the first encounter with the enemy.

I am inspired to share a couple of observations on how we need to overcome the tendency to over analyse and to encourage everybody to fight back against analysis paralysis.

That inspiration is driven by a trinity of positives: listening to a great podcast from Tim Ferris where he hosted General Stanley McChrystal, a reminder of some of the words of the late General Colin Powell and a walk down memory lane from Goldman Sachs days when on a major project we had to take a leap and go with our gut.

All help to inspire me on days when I have to do battle with the over-analysers. It doesn’t have to be this way and it should not be this way. I hope these thoughts give you some inspiration too. #JFDI and #don’tletthebuggersgrindyoudown.

We may well have known, unknowns and questions we’d love to ask. And, the over-analysers don’t want to make any decision until they have all the answers. The late General Colin Powell formulated his wisdom in 18 Leadership Lessons. He observed that excessive delays in the name of information gathering breed analysis paralysis and that procrastination in the name of reducing risk actually increases it. He offered a two-step approach to strike the right balance between analysis and speed of response.

“Step I: Use the formula P=40 to 70, in which P stands for the probability of success and the numbers indicate the percentage of information acquired.

Step II: Once the information is in the 40 to 70 range, go with your gut.”

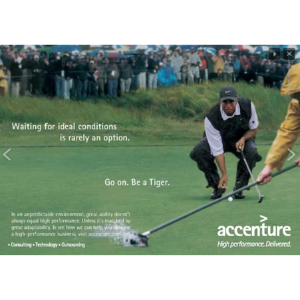

In his prime, the great golfer Tiger Woods, worked with the consultants Accenture. Now, whilst the consultants are prone to glossy analysis and a multi-page PowerPoint deck, this image perfectly captures the need to make decisions even in imperfect situations.

Ability needs to be matched by adaptability.

Source: Accenture Calendar 1

Adaptability is at the centre of the thinking which General Stanley McChrystal shared with Podcast host General Stanley McChrystal. The general, a four star, led the US military effort in Afghanistan from 2009. In 2021, McChrystal published his latest book Risk: A User’s Guide. One headline note from it sets out his stall: “The idea that we want to mitigate risk to zero before we act is really common and really costly.” Tim Ferris asked him how he would train 100 athletes to be great soldiers. The general picked three areas of focus: endurance, live fire training and making decisions with incomplete information, where they would be forced into bad outcomes and need to deal with them.

The general also recounted how folks in Washington, the “higher ups”, had a recurring MO for kicking the can down the road. McChrystal recalls how often his team would present a case for acting now against terrorists. One or other bureaucrat would then ask: “”Let me ask a couple of questions, how much wood can a wood-chuck chuck? We need more information”. Once the requested information was gathered, the opportunity was missed. The bureaucrat would then berate the general, telling him: “You need to come better prepared, so I can approve the decision.”

The psychology of that kind of exchange is very much about not making a decision. There is an old adage about things IT: “nobody ever got shot for buying IBM”.

In other words, doing the same old, the expected thing is fine. That approach has an implicit corollary: “Nobody ever got shot for not buying or not doing not IBM”. It is hard to get in to trouble for not doing anything. It is also unlikely you get found too soon for not doing something. That is the story of generations of government officials in London who do not invest in infrastructure, leaving the great overhaul of the water pipes to future generations.

My own modest contribution to this genre is away from the battlefield of armies to that of financial services institutions and their internal decision-making processes. This goes back in the annals of history to the mid ‘90s and my time at Goldman Sachs. The Swiss Stock Exchange had announced plans to move to electronic trading. This had the very smart team in Equity Derivatives positively salivating; more activity, & faster trading would boost profits. That and applying some not considerable pressure to yours truly to sort this out; #JFDI.

The very nice folks at the Exchange though wanted to extract their 454 grammes of flesh. In late 1993, they issued an edict that required Goldman to be part of the existing, physical floor-based exchange before being allowed into their new exchange, which they’d dubbed EBS. The requirement was to have “brogues on the floor” by the end of October 1994.

That led to the traders turning to me and saying in no uncertain terms how I had to make sure we were there and able to collect our “future EBS member” admission ticket. In Operations, we had seen this coming and done some preliminary analysis. There were various consequences which included a need to replace the internal settlement & custody system we had. Some older readers might wince in sympathy when I recall that we were operating a business with a turnover of hundreds of millions per day on something strung together on Foxbase and Paradox.

So, we engaged with Equities IT. The whole thing got stuck in the mud of institutional inertia. They looked at this, they looked at that, they even thought they could and might build it themselves, and in all of this they started to solve for all of Operations globally, not just our outpost in Zurich. Time dragged on, as it does, with no decision. The most senior IT leader involved was known internally as NATO, no action talk only, so we were not entirely surprised.

In February 1994, with the clock ticking, myself and our local IT leader were summoned to London to look at a system called Gloss from Wilco (Ed: now part of Broadridge). Equities IT thought this might be the holy grail for all of Equities Operations. That said, one local London lad was firmly of the opinion that “this will never do UK Equities”.

We did our due diligence; the system was not pretty, but I could sense it had many of the Lego parts we needed, albeit with a user interface that was more yuk than GUI and would be an insult to our team, but we could fix that. On the way back to the hotel after several grinding days of demos, I asked my IT partner, Joe Gruss: “Joe, do you think this thing can do more than 50% of what we need?”. He answered that he thought it could and that we could find a way to deal with the rest, somehow or other. TBD as it were.

I picked up the phone and called the Head of Equities IT. “We can make this work for Zurich. We’ll take it and be the pilot installation in the firm”. With that, we were proverbially off to the races. We replaced all the systems and made the deadline to be at the Exchange.

In the process, we had a lot of fun. We literally had a garage project, well actually 14 people crammed into a small room in a town house off Chiswell Street in London. Many lasting friendships stem from that intense effort: Fred Gedling, Mark Petronino, Craig Spendiff, Donal O’Brien, Terry Williams, Ian Stephenson, Patrick Sockett, Erwin Adank, Valerio Di Bari, Marcel Estermann and Gianni Quaglia, thank you very much for your part in all of that.

Lessons to be learned

That challenge of “does it do more than 50%” came before I read General Colin Powell’s leadership words or heard those of General Stanley McChrystal. The Tiger Woods ad too would come later. I have a framed copy of that poster in my office. It feels good to see my own approach supported by such luminaries and even better to see it articulated so well.

Even if it is somehow possible to mitigate risk to zero, I would put the case that it is seldom the case that you have the luxury of time and even money to do all that analysis now. Better to do enough analysis, be clear about the known unknowns and move quickly to the next stage.

“The best is the enemy of the good.” This is a great mantra. Of course, we all like the best and want to do our best. “Best” is though not the only benchmark. In the world. In setting the bar, the relatively young discipline of agile offers useful guidance. ‘The term “definition of done” is a much more useful guide to setting the “hurdle rate”; a level of completion and detail is defined that is enough for the current maturity of the task at hand.

This is a lesson I am indebted to the very agile Stephen Ram at Cedus for hammering home. Importantly, the focus is on the desired current level maturity. You accept there will be a need for more detail later, and you accept the limitations which go with what you do today.

A final note: the success we had at Goldman Sachs was the result of great work from a whole team of internal and external folks. Holding all the tech side together and getting us across the line was my IT partner-in-crime of that era, Joe Gruss. Sadly, he died shortly after our big success together. Tragically and too young. Lynn & Laura, if you happen to read this, you should know how much I value that time with Joe and still think of those times.

About the Author: The Bankers’ Plumber. I help banks and FinTechs master their processing; optimising control, capacity and cost.

If it exists and is not working, I analyse it, design optimised processes and guide the work to get to optimal. If there is a new product or business, I work to identify the target operating model and design the business architecture to deliver those optimal processes and the customer experience.

I am an expert-generalist in FS matters. I understand the full front-to-back and end-to-end impact of what we do in banks. That allows me to build the best processes for my clients; ones that deliver on the three key dimensions of Operations: control, capacity and cost.

Previous Posts

Are available on the 3C Advisory website, click here.

Publications

The Bankers’ Plumber’s Handbook

Control in banks. How to do operations properly.

For some in the FS world, it is too late. For most, understanding how to make things work properly is a good investment of their time.

My book tries to make it easy for you and includes a collection of real life, true stories from 30 years of adventures in banking around the world. True tales of Goldman Sachs and collecting money from the mob, losing $2m of the partners’ money and still keeping my job and keeping an eye on traders with evil intentions.

So, you might like the tool kit, you might like the stories or you might only like the glossary, which one of my friends kindly said was worth the price of the book on its own. Or you might like all of it.

Go ahead, get your copy!

Hard Copy via Create Space: Click here

Soft copy via Download: Click here

Share on: